Sharing is caring!

Do your students struggle with compare and contrast activities? Maybe they rely on the obvious at the expense of analysis? Is thesis writing, constructing outlines, and avoiding plagiarism a problem? If you answered yes to any or all of the questions, you’re not alone! My students struggled big time with comparative essay writing and so I had to hone how to teach compare and contrast skills! Let me share some of my learning with you, and by extension, your students!

How to Look Beyond The Obvious

This seems like obvious advice but I was surprised by just how much my students skated on the surface of a topic when they were trying to compare them as opposed to when they had to analyze a single text. It seemed like the same skill at work to me but for them, it was as though I was asking them to skip a step – to jump right from reading to explaining how are they different/same.

So you might need to take a step back and have students focus, really focus, on a single text before they even attempt to compare it to another.

For example, when I want students to compare apples and oranges I’m not going to ask them to compare apples and oranges! Instead, I’m going to get them to share everything they know or can learn about apples, then we take a pause, and return to do the same with oranges. This way, there’s data or info to pull from when we shift to comparing.

To dig a little deeper into the data/info they have, a guiding statement for students in this early phase of their task is to look for similarities where there are obvious differences and to look for differences where there are obvious differences.

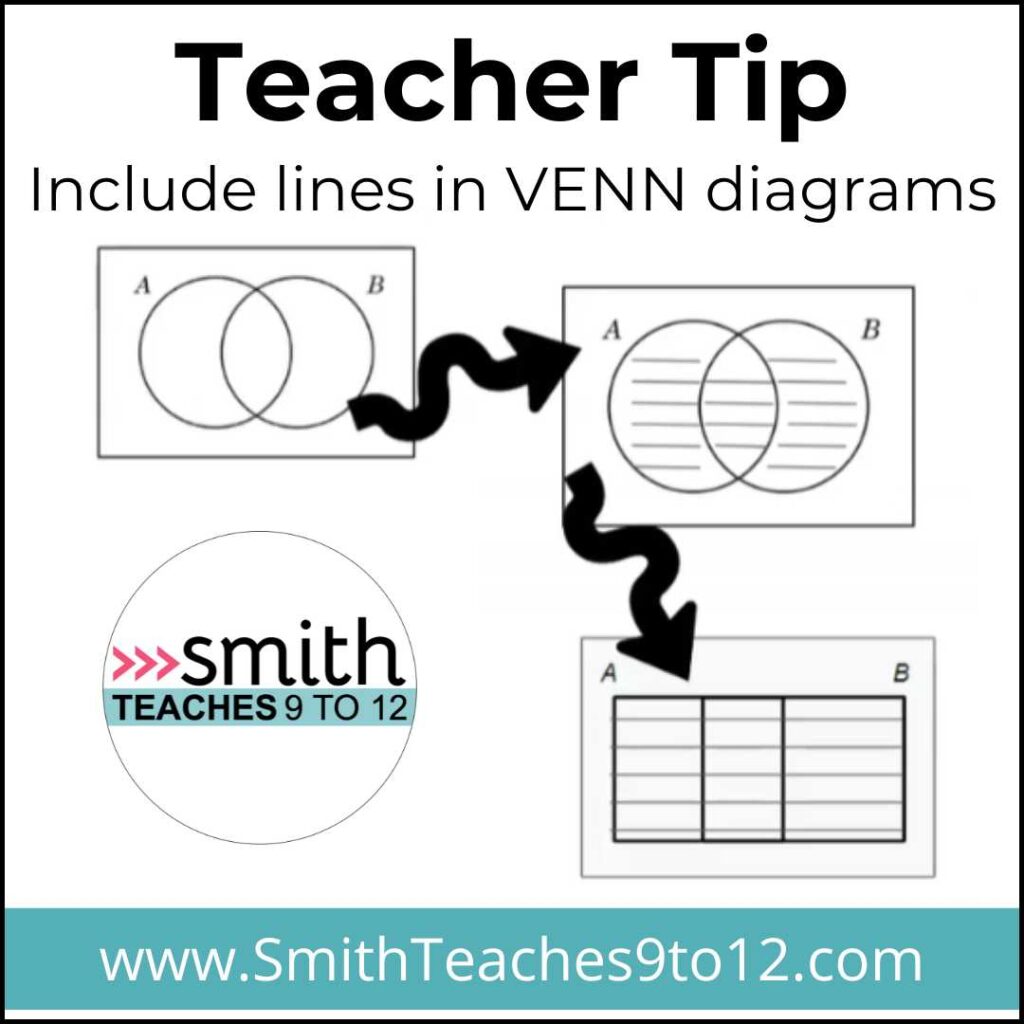

Once they do this, get them to fill out a Venn diagram. A graphic organizer like this is helpful for student organization and teacher check-ins.

TEACHER TIP: With VENN diagrams, shift from circles to rectangles and include lines for students to write on in those rectangles. This provides a bit more structure for those who need it and it gives more space to write too!

Let’s go back to our apples and oranges. Both are round fruits that grow on trees. Sure this compares them but it doesn’t offer a contrast. So looking beyond the obvious will open that up. Consider that oranges are grown in warmer climates whereas apples flourish in more temperate climes. This has now contrasted (on a simple level) the two items. Push a bit more to ask ‘why’ this might be and it can lead to the analysis that’s necessary for a strong comparative essay.

These two shifts usually lead to more depth and better analysis in the final product.

How to Write Comparative Thesis Statements

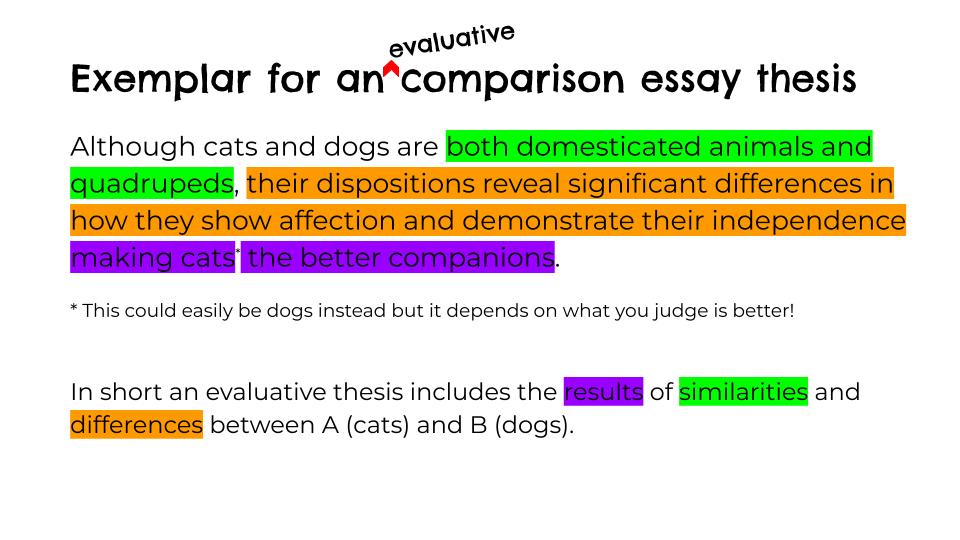

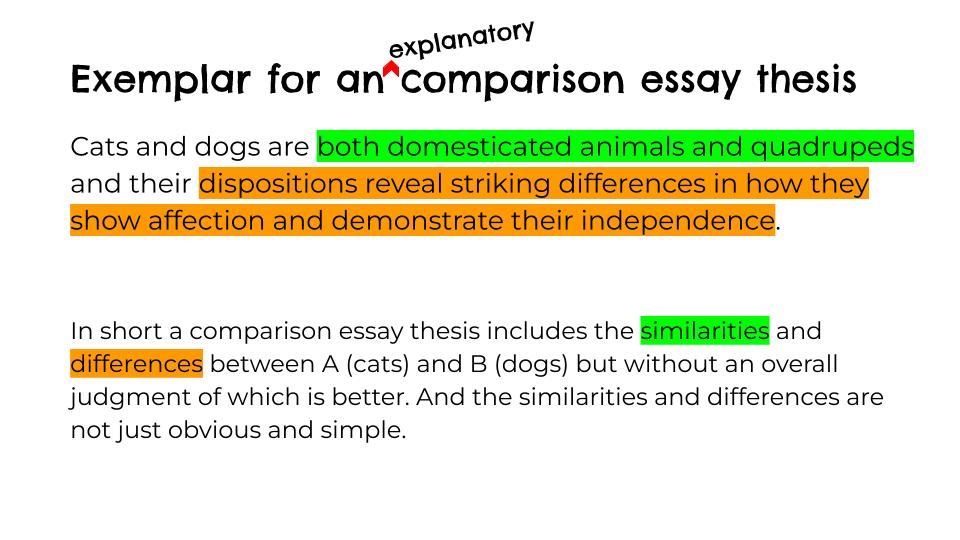

Next is drafting a thesis statement. A thesis for a comparison essay is a bit different than your average thesis. There are two thesis options for comparison essays: evaluative, which includes the results of similarities and differences between A and B, and explanatory, which includes an examination of the similarities and differences between A and B. With all things, there’s a time and a place for each.

To help students at the beginning of their writing journey, provide a sentence frame for the thesis that’s needed. Those who need it will use it and those who may not need it can use it more like a mentor sentence to draft their own.

The sentence frame can be simple! Check out these two examples that are color-coded.

TEACHER TIP: Get your students to color-code their work too. They can do this with their thesis and then continue with their full essay. This helps as a self-check and can make your teacher life WAY easier when evaluating the assignment!

EXTRA TEACHER TIP: Click here for a complete thesis lesson for comparative essays designed to help your students and save you time and effort!

How to Structure An Essay

Once students have a thesis, remind them this might change as they start outlining their full essay. Then get them to move to an outline. Students want to dive in but that usually means they’re working harder and not smarter. An outline – a good outline – is where to invest time so that when it comes to writing the final product, the points and evidence are there without having to search.

Students might choose to use either a block or an alternating structure. Block structure groups together each text whereas an alternating structure shifts from text to text and back in order to address the similarities and differences. Don’t reinvent the wheel, grab your own digital and print versions of the two types of outlines, with a lesson on hooks and clinchers too!

How to Avoid Plagiarism

As English teachers, we know this happens ALL. THE. TIME! Here’s some of my best advice to avoid plagiarism:

1. Location, location, location

Write the assignment in class either by hand or online so you can access it through your learning management system.

2. Regular (short) check-ins

Do check-ins with students throughout the process. The evaluation of an assignment shouldn’t only happen at the end. Check-ins mean you can see where students are struggling and offer support along the way – the Venn diagram, thesis, outline, and then the writing process. You don’t need to collect anything to grade unless you want to incorporate process work into your grading scheme, just use a simple checklist with student names and checkboxes like this one (click to make your own copy of this freebie!).

Only grading an assignment at the end of the process is akin to an autopsy, whereas check-ins – even ones that are short and sweet – are like seeing the doctor to get a diagnosis before a situation really becomes problematic!

Over the years, I have found that plagiarism is more often than not really a result of struggles with time, understanding, or (academic) pressure. A check-in along the way can help resolve these issues most of the time and therefore avoid plagiarism.

3. Try the road less traveled

Be wise with your comparison topics (or any assignment’s topic). While I know it’s not always possible to choose the texts you’re going to teach, you can make adjustments.

One option is to break apart the grading. This means you can focus on how students grasp the skill of comparing texts with “off-curriculum” texts or ones that are lesser or not known in the online world. I choose poetry for this and even then lesser-known but still accessible poetry. Here’s a lesson plan that focuses on three poems around the same subject – advice to girls – with different approaches. These poems are readily available online but analysis of them is not so the work to compare and contrast will have to be the students’ own!

Then when they have to compare text A and text B which are SUPER common and have tons of materials available online, you can focus on essay structure – paragraphs, intro/conclusion, transitions, rather than specifically on content.

Here’s hoping some of my lessons learned along the way can help you in your ELA classroom as you and your students tackle comparative essay writing this year!

AND… If you want to make all of this happen in your classroom but avoid the big investment of time and effort, then check out this compare and contrast lesson bundle. It includes all of the lessons outlined in this post – poetry, thesis writing, digital and printable outlines, plus a final assignment with editable rubric, and even feedback stickers for during and after the process!